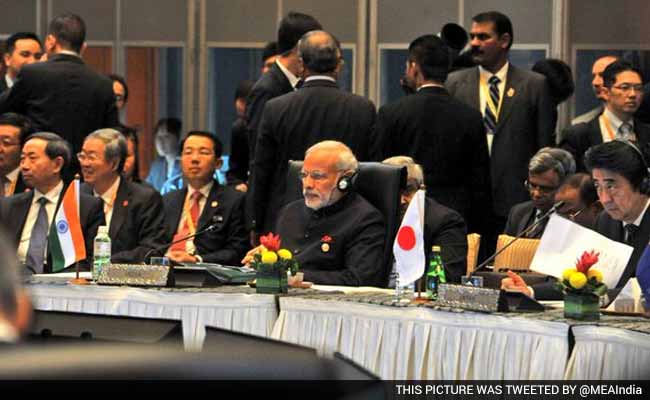

(At the ASEAN summit in Manila)

Love to repeat what’s become my favourite line — I TOLD YOU SO!

Immediately after his nomination by the Republican Party as its presidential candidate I had written that once in the White House, Donald Trump would be so self-centered and concerned only with advancing America’s narrow interests that Delhi should pragmatically prepare to get out of its traditional policy of leaning on big powers — the Soviet Union pre-Cold War end and in the new century, the US — for the country’s strategic security, and begin relying on itself and its national resources for its own protection because it will be compelled by the emerging circumstances to do so anyway. And hence, that Trump’s election would be a good thing because, finally, the value of self-reliance, especially in arms and national security, will be appreciated. (“Why Donald Trump is good for India”, Open magazine 20 July 2016, http://www.openthemagazine.com/article/politics/why-donald-trump-is-good-for-india and also posted on this blog).

Such tocsins that I sounded have, however, gone unheeded. Now that Trump has dumped on the Narendra Modi regime and other friendly states, leaving them high and dry, perhaps, some one in PMO, MEA, government will. The prompt is the decision by the President abruptly to withdraw the US military from Syria and Afghanistan. Defence Secretary, James Mattis, objected and resigned. He was the only man standing between India and Trump’s whimsicality.

So, consider the situation now: In Afghanistan, the Modi government suddenly finds it has lots of now hollow promises about sustained US commitment to realizing a Taliban-mukt Afghanistan and no US boots on the ground to achieve it. India has lost the military cover under which Delhi was running its own Afghan Taliban links. Oh, sure, Trump will leave a few Special Forces units in Afghanistan (and in Syria) to prosecute counter-terrorism( and anti-IS) actions, but for all intents and purposes the US has abandoned Afghanistan, leaving the Kabul government of Ashraf Ghani in a lurch, and the Pakistan-leaning sections of Taliban in that country ascendant. In the last such Taliban rule by the one-eyed Mullah Omar, terrorists professing the Kashmir cause hijacked an Air India flight to Kandahar leading to capitulation by the previous BJP government and the sheer humiliation of External Affairs minister Jaswant Singh handing over Azhar Mahmood to the Taliban.

With the Taliban-run Afghanistan once again available as a base in-depth, Inter-Service Intelligence of the Pakistan Army will be in a position to marshal that country’s vast terrorist resources in terms of religiously motivated manpower. Whether Indian intelligence agencies in league with other outfits can prevent such a denouement is doubtful. In the main because the sections of the Afghan Taliban, whose members also join up opportunistically with the Pakistani Taliban that Indian intel have cultivated over the years, are incapable of outfighting on two fronts — against the more rabid Taliban in Afghanistan and the Pakistan army in Pakistan. But India would have to keep a hand in in Afghan affairs by sustaining the friendly Taliban in the field. However, the best diplomatic bet for a solution is the underway Russian initiative for peace in Afghanistan. Nov 8 meeting hosted in Moscow by the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov had invitees from United States, India, Iran, China and Pakistan, and the five former Central Asian republics, and hailed the meeting as an opportunity to “open a new page” in Afghanistan’s history. India’s role, insofar as can be made out, was just to mark its presence.

The Afghan escapade pulled by Trump meshing with his Syria decision was justified via twitter thus: “Why are we fighting for our enemy, Syria, by staying & killing ISIS for them, Russia, Iran & other locals? Time to focus on our Country & bring our youth back home where they belong!” In other words, the Islamic State core fighting forces and leadership, who are supposed to have bolted with a full load of hard currency and gold from their Syrian and Iraqi strongholds, are readying to renew jihad against darul harb (non-Islamic world) but Washington wants no part of it. Except this fight can seep into the Kashmir dispute. How?

Because Hindu India oppressing Muslims is a cause Islamists from all over can readily rally around. What with Adityanath and his hate Muslim-antics in Uttar Pradesh providing almost a pluperfect basis for the already active Islamic State, J&K branch, to base their war against the Indian state on. And because, an effete Indian state would seem to be an easy target for an IS-led international movement hungry for success after its thrashing in their West Asian redoubts by the combined military might of US, Europe, Iraqi forces loyal to Baghdad, and assorted Arab states, with the Saudis in the van, and Turkey seeking to lead this campaign. Indeed Recep Erdogan, with a subconscious motive of reclaiming the Ottoman domain in some sense has, in fact, been handed the helmsmanship of the fight against IS rump by Trump who has decamped from the region along with the US forces. With Ankara so elevated and Turkey’s intimacy with the powers that be in Islamabad (read Pakistan army) set aside the cold vibes Erdogan encountered when he visited Delhi and broached the topic of mediating on Kashmir, he may not be altogether averse to channeling the IS fighting horde, via a facilitative Talibanized Afghanistan, into Kashmir.

How does Modiji expect to deal with this onrushing train when his policy is tied to the rails of ‘strategic partnership’ with a completely unreliable and untrustworthy America? We will nevertheless hear from the Carnegie-Brookings crowd, including its leading lights here and in nearby countries via op/eds in Indian newspapers who will twist these developments and Trump’s wayward policy into a pretzel to argue that Delhi should tie India even closer to the US to reap strategic rewards, when the time actually is nigh for India to begin securing its future by itself.

At the heart of this policy mess is the fact that Indian politicians and the Indian government invariably make a hash of reading the United States correctly. In the main because, like Modi and everybody else in policy making circles, dependency on external players is instinctive, laced with personal profit, aspirations, and desires that are made to fit inconvenient reality. In this case, it has resulted in India giving in to Washington on every issue, playing the doormat, and making no substantive move to incentivize the states on China’s periphery to join together in shoring up our individual security by collective means. “Look East, Act East”, in the event, is just another slogan to be trotted out the next time a summit takes place in those parts or a head of state from there comes visiting.

India has much in its corner. It has military access to Duqm in Oman, the French Base Heron in Djibouti, Seychelles, Maldives, Trincomalee in Sri Lanka, Sabang in Indonesia and Na Thrang on the central coast of Vietnam, and the Indian Navy has worked up these and other maritime neighbours in its Indian Ocean Naval Symposium into a cooperative mood, but where’s the follow up action? What’s the point of these bases on distant shores if no Indian military forces are ever posted there?

Inaction always has cost. Tajikistan offered the Farkhor air base in Ainee for India to refurbish and to operate a squadron of IAF Su-30s out of. Had this squadron been immediately posted to Ainee soon after an Indian task force in the early 2000s had lengthened the runway to handle heavier aircraft and redone the tarmac — all with Indian monies, India would have had a military grip on China’s flank. Instead Delhi waited, displaying its usual lassitude, and IAF did nothing to prod the Manmohan Singh government into approving such deployment and, voila!, the Russians returned in this decade militarily to recover Ainee for their own use as a forward base. So now if Delhi invokes its original understanding with Dushanabe, Moscow may, depending on whether relations with India are frosty, exercise a veto.

This is how every extra-territorial military initiative that Delhi mounted has ended. In the maritime domain, for instance. Mozambique’s request to the Indian government to found a navy for that country equipped with phased out Indian corvettes and frigates and led by Indian Navy officers remains unaddressed from the time it was first made in the year 2000. That’s the sort of urgency the Indian government shows for anything remotely strategic! The Indian people’s dream of India as a great power is wrecked by such care-less attitude and sheer disinterest in doing anything worthwhile.