As predicted in my last post, the extended S. Jaishankar-Wang Yi pow-wow in Moscow that reportedly concluded well after midnight, India-time, in substantive terms produced zilch. Keeping in mind Russian sensitivities and the Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov’s determination to see the two not end their meeting with nothing, the Indian and Chinese minister reached a laboured 5-point agreement that far from brightening the prospects of peace may have set the scene for more military exchanges in eastern Ladakh. Depending on what transpires and however the intensity and scale get ratcheted up by the forward units of either side, we may yet have full bore hostilities.

Consider the five points (The text of the agreement at the MEA site, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/32961/Joint_Press_Statement__Meeting_of_External_Affairs_Minister_and_the_Foreign_Minister_of_China_September_10_2020.)

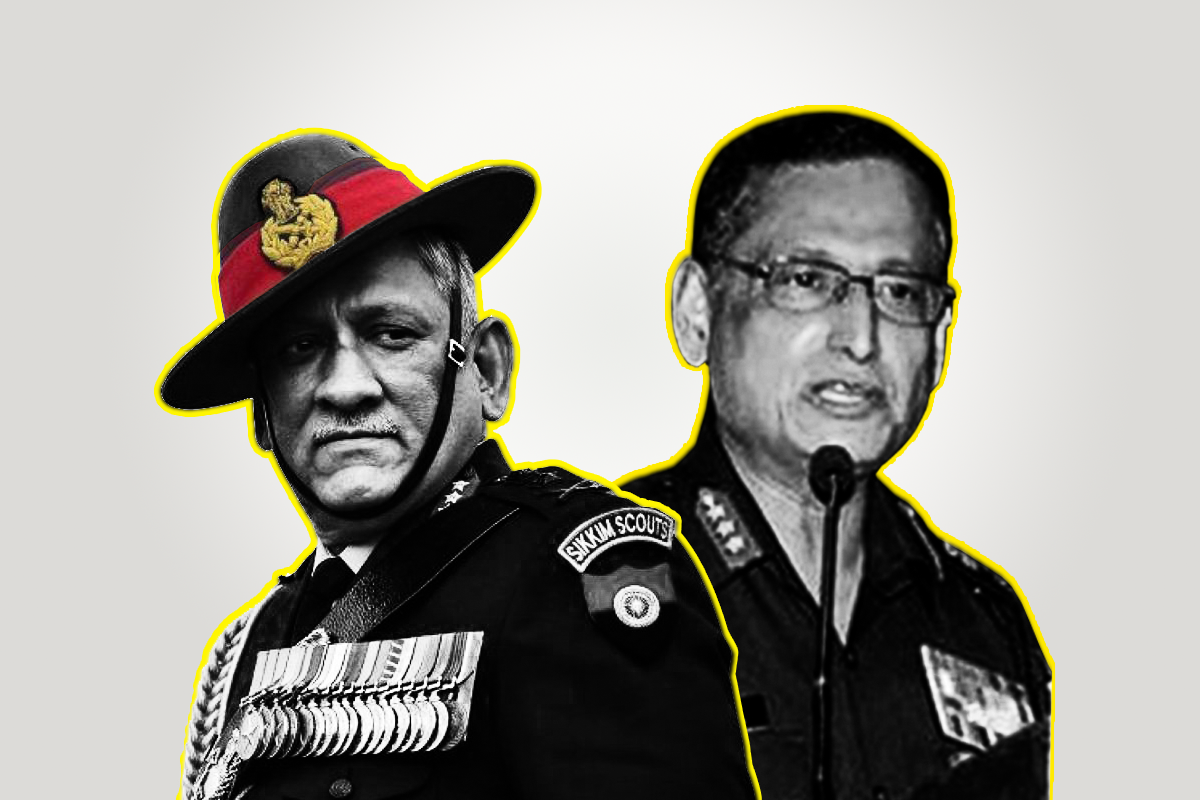

The first point repeated the tired line of “not allowing differences to become disputes” — Jaishankar’s signature tune. The second, cleverly from the Chinese point of view, puts the onus on the military level talks — yes, the same patience-sapping talkathons conducted in Moldo-Chushul by the XIV Corps commander Lt Gen Harinder Singh and Major General Liu Lin, PLA in-charge of the southwestern border sector, and at less senior levels — to reach a modus vivendi and “quickly disengage, maintain proper distance and ease tensions”. The third point features the Indian government’s insistence that both sides “abide by all the existing agreements and protocol on China-India boundary affairs” starting with the 1993 peace and tranquillity agreement “in the border areas and avoid any action that could escalate matters” — though the 1993 accord is nowhere mentioned. In the fourth point, they agreed that the military-to-military interactions continue, on parallel tracks, with the Special Representatives level talks and the WMCC (Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination) meetings. And the final point, putting cart before the horse, voiced the unwarranted hope that the two countries “expedite work to conclude new Confidence Building Measures”.

That the 5-points mean little was stressed by Wang who, in response to Jaishankar’s saying that India “would not countenance any attempt to change the status quo unilaterally” and expressing his desire that bilateral ties resume their earlier “largely positive trajectory”, reiterated China’s “stern position” on the situation in the border areas. He emphasised “that the imperative is to immediately stop provocations such as firing and other dangerous actions that violate the commitments made by the two sides”, adding that it is also “important to move back all personnel and equipment that have trespassed” and the “frontier troops must quickly disengage so that the situation may de-escalate”. Meaning, that Beijing will not compromise a whit on its stance that because Indian troops violated the LAC, they’d have to withdraw to obtain peace premised on Delhi accepting the new LAC secured by the PLA. This frontally contradicts the Indian government’s goal articulated by Jaishankar June 17 of restoring “the status quo” as existed in Ladakh in April 2020.

It is clear though what the Chinese strategy is in the non-military sphere. It is to sow confusion with a plethora of negotiations — each negotiating channel, at least on the Indian side, getting in the way of every other, and seeding a mess that Indian official and military circles will be preoccupied with, while Beijing conveys the impression of progress being made, however haltingly, in this or that or the other channel. As mentioned in the previous post, at the apex level Wang Yi is discussing ways to resolve issues simultaneously with Jaishankar and with the NSA, Ajit Doval. Why Delhi agreed to this twin-apex track in the first place many years ago is not a mystery. In theory, the National Security Adviser in the PMO has the ears of the prime minister — the only person in the Indian system who counts — and is the channel the PM can use for directed intervention bypassing the bureaucratic maze in MEA. So far, some 22-23 sessions of the Special Representatives level talks have been held with nothing to show for them. And it doesn’t seem to matter if the NSA is a Mandarin-speaking China expert or not. Doval was preceded as Special Representative by Shivshankar Menon — NSA to Manmohan Singh, and former Foreign Secretary, who cut his diplomatic teeth in China. It made no difference — there are no results.

That China nevertheless is happy plugging for multiple active negotiating streams suggests they serve China’s purpose, not India’s. It is time Delhi called a halt to this farce of negotiations, and restricted all negotiating with the Chinese to a single forum, a unitariness of command Beijing has achieved by making Wang the go-to guy even as on the Indian side there’s a whole bunch of people mucking up the works. So, the negotiating strategy needs to be sorted out.

To add to India’s troubles, the two principals while alighting on the 5 points in Moscow entirely ignored the fluid reality on the ground in eastern Ladakh, which is hurtling towards some serious military engagements. Except, no one on the Indian side seems to be very clear about what the field reality is, not even the army.

Consider the situation on the north shore of the Pangong Lake. Per press reports, there is supposedly an Indian troop concentration on the Finger 3 ridge to match the strength of the Chinese force on Finger 4 and to deter it from advancing towards Finger 3 via the connecting “knuckle” — the site where the two sides are presently facing each other at not too great distance. But what is really confusing is the Indian army sources have told the press that the PLA is physically blocking Indian troops from reaching a high point — presumably the highest point — on Finger 3 ridge by suddenly appearing with flags every time an Indian detail tries to reach it. (Refer https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/pangong-fingers-hot-up-scramble-for heights-as-pla-men-mass-on-ridge-india-sends-more-troops-6591327/ )

So what is it? Are Indian troops really in control of all of the Finger 3 area or not, the knuckle connecting the fingers apart? Because if the PLA is entrenched on Ginger 4 alone, how can they suddenly appear on Finger 3?

Or, is it an unpalatable truth the army is unwilling to own up to that it has lost or nearly lost all of Finger 3 to the PLA as well? Or, if this feature has not been wholly lost, that the Chinese military units have been somehow allowed to get on the Finger 3 ridge? Because a source in the above-mentioned news story is reported as saying: “The assessment was that sooner than later, the Chinese would descend to cut off our access to Dhan Singh Thapa Post. We had to make sure they were blocked. Now along the entire Finger 3 ridge, Indian troop strength has been increased at different places to match the Chinese.”

If Finger 3 is being contested with the PLA, besides the Major Dhan Singh Thapa post at the foot and on the western side of Finger 3, Indian military presence in, and control of, Fingers 1 and 2 too are imperilled. After all, if the Chinese have taken Finger 3, why would they not try and also push Indian troops out of Fingers 1 & 2, thereby occupying all of the northern shore and completing a route of the Indian army? This reading of the situation fits in with HQ XIV Corps’ apparent belief that the PLA will seek to displace Indian troops from the Finger 3 ridge and add it to all the Indian territory already annexed to the west of it — the extended area from Fingers 4 to 8. Still, Indian military sources explain these aggressive PLA moves as merely a reaction to the Indian occupation post-August 29 of the commanding heights on the Kailash range around Spanggur Lake, proximal to the south bank of the P-Tso. This has only heightened the uncertainty about what’s happening as regards these hilly spurs on the Pangong.

Of course, the Chinese encroachment and permanent occupation of all the Fingers is a worrying prospect, and vacating the PLA from these areas will be a fairly major military undertaking. But the move to contest Finger 3 (and logically also Fingers 1& 2) could be a feint, to divert the Indian military’s focus and resources from the Kailash range that makes the disposition of Chinese forces on the Spanggur Tso and the southern end of Pangong untenable.

The fact is realizing the government’s objective of status quo ante will require the army to vacate the PLA from Fingers 4 to 8, remove Chinese troops from the Y-junction in the Depsang Plains, and PLA presence from the Galwan Valley and the Hot Springs-Gogra-Khugrang area, and protecting the DBO highway by securing the mountain heights on the eastern bank of the Shyok River, will necessitate the Indian army being more aggressive and proactive.

One can only hope the preemptive occupation and fortifying of Black Top and other heights in the Kailash range was not a one-off thing — a rare island of aggression in an otherwise bland sea of caution.

HAL_H2020022786385.JPG)