[Modi and the new Australian PM, Anthony Albanese]

One of the reasons the outgoing Conservative party prime minister Scott Morrison quickly conceded the elections was to give Canberra the time to prep the incoming Labour party PM, Anthony Albanese, for the Tokyo summit of the Quadrilateral heads of government, May 23-25. But, however, successful the Australian Foreign Office is in bringing Albanese upto speed, it is unlikely he will have crystalized his party’s views on anything as to begin negotiating substantively with his Quad counterparts, even less to commiting Australia to new initiatives. Especially because, it is still not certain that the ruling Labour Party will have a majority and have its own government, or whether Albanese will have to make-do with a coalition government with smaller parties and independents, which will necessitate policy compromises.

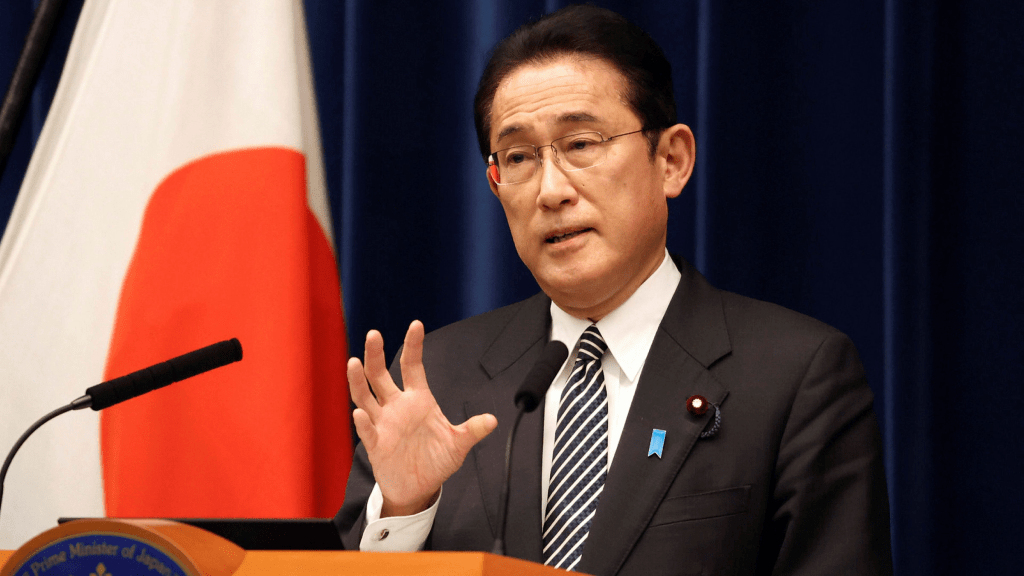

In the event, much of the summit will be spent with the Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, US President Joe Biden, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who technically is the most experienced of this lot of leaders in both foreign and military policy fields, getting to know the new Australian leader. Kishida was foreign minister from 2012 to 2016 in Shinzo Abe’s government and in 2017 pulled time as Japan’s defence minister.

But niceties apart, there are certain things about Albanese that will help him resonate with Modi. In his acceptance speech, he reminded the audience about his humble background — he grew up with his mother who is a “welfare pensioner” — something that’s bound to stir Modi’s empathy and fellow-feeling. Moreover, his promise to make his country “a renewable energy superpower” — meaning hydrogen, solar and wind power, parallels Modi’s own agenda of making India a leading “hydrogen power” by 2050. This could be the context for substantive collaboration in developing renewable energy technologies and, foreign policy-wise, will be the low-hanging fruit Modi and Albanese can pluck.

However, on issues relating to the Quad’s raison d’etre — containing China by all means, particularly military, there may be chasm between Australia and the other Quad members. With Morrison’s single-minded security-oriented approach missing from the Tokyo pow-wows, a wishy-washy attitude may prevail vis a vis collaring China. The work will thus be cut out for Biden to persuade Albanese to, at least, continue with Morrison’s policy of permitting the northern Australian coast to be built up as an extended staging area for American and other Quad air, naval, and land forces. In fact, to thwart the Chinese PLA, navy and air force from acting up in the South China Sea and, precipitously, against Taiwan, the US Army already has over a thousand troops stationed in Darwin. This port is also being configured to host US navy’s nuclear-powered attack and cruise and ballistic missile-firing submarines. How Albanese will dovetail these aspects with his government’s economic imperative to ease relations with China,is a matter of conjecture.

But given that the Australian economy has slowed down considerably — the main reason for Morrison and his party losing the elctions — and is in need of a quick “pick me up”, reopening the Australian market to Chinese goods is a fix Albanese will opt for. Chinese exports in the last 20 years registered a double digit annualised growth rate, in 2020 touching some $58 billion. In turn, Albanese will hope Beijing opens the tap for Chinese investments in the extractive and other industries and otherwise kick-start the Australian economy. Aware of the wind blowing its way, Beijing has already begun to incentivize this trend by increasing Australian revenues from importing, in the main, Australian grain, gas, iron ore, and coal. The intent, no doubt, being to weaken the security cooperation aspects of the Quad that the Xi Jinping regime has publicly voiced its displeaure against. Indeed, it is the fear of provokng China that thas resulted in both Delhi and Tokyo tippy-toeing around the military objectives of the Quad.

[Prime Minister Fumio Kishida]

And it is precisely this fear of China that has been the biggest stumbling block in ratcheting up the India-Japan strategic partnership. In Japan’s case, because it now also has a potentially rogue Russia run by Vladimir Putin, in a raggedy war in Ukraine in which the Russian army, for whatever reasons, has still not conducted an all-fronts smash-up campaign, potentially lashing out, as Tokyo suspects and, suicidally, opening another front on the Kurile Islands. This in any case is a contingency Tokyo is becoming alive to.

In India’s case, it is because of the Indian government’s and the Indian military’s seeming inability to think and act strategically — now part of their DNA. The chance for a really China-constrictor set-up was provided by Abe — the first Asian leader in recent times with a truly strategic bent of mind. In 2007, in his second year in his first short tenure of 2 years as prime minister he proposed the “security diamond”. He did so not in the US or in any European forum or even from a prestigious platform in his native Tokyo, but in his address to the Indian Parliament. It indicated the centrality he accorded India. Elected back to power in 2012 for a longer run as prime minister, a post he voluntarily vacated in 2020, Abe worked on that “security diamond”, fashioning it with Washington into the more practicable (and less abstract) Quadrilateral.

Tragically, that Quadrilateral, has been running in place and going nowhere since, in part because it lacks a military mission and motor which, in turn, can be attributed to Modi picking the wrong project to prioritise from among the items offered India by Abe during his January 2014 state visit — four months before Modi swept into power. In the following years, as flagship of the strategic partnership, Modi chose to install the Shinkansen highspeed railway connecting Mumbai to Ahmedabad with Japanese credit worth $15 billion rather than use that money to set up a plant to produce the Shinmaywa short takeoff US-2 multirole maritime aircraft and its spares to meet the Indian Navy’s needs as well as the global demand!

Unanimously rated the best such aircraft in the world, the US-2 is adept variously in surveillance and reconnaissance, in the antiship attack role, in landing on a coin anywhere, including near oil rigs carrying provisions, repair material or rotational crews, or next to smuggler dhows or motorised craft carrying terrorists for seaborne attack (as on Mumbai 26/11 in 2008) or Somali pirates operating off Aden, allowing the on-board marine commando (MARCOS) in the latter instances to take care of business, or even to airlift Special Forces for expeditionary tasks on the Indo-Pacific littoral or in protection of friendly island-nations (Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles, Sri Lanka). It can do all this in really rough sea conditions, and is the pluperfect platform for patrolling and protecting 24/7 the country’s 572 widely dispersed island territories in the Bay of Bengal, the Andaman Sea and in the Arabian Sea.

So, what does the most strategic-minded among the Indian armed services — the Indian Navy, do? it rejects Japan’s US-2 project, saying its immediate requirement of just 12 US-2s did not justify such expenditure and that it’d stick with the antiquated Dornier 228s instead. The Navy has understated its US-2 requirement. Just as replacement for the Dorniers, the Navy alone will need 27 US-2s and the Indian Coast Guard another 17, for a total of 44 US-2s — a very respectable first order for the Indian-built flying boat. But no, 12 is the number the Navy stuck to, never mind the full technology transfer and manufacturing wherewithal and training that Japan promised, or the contract for supply of Indian-made spares for US-2s everywhere, and even grant-in Japanese aid to finance the whole deal! (The US-2 fiasco is detailed in my 2018 book — Staggering Forward: Narendra Modi and India’s Global Ambition, pp. 256-269.)

Hardly to be wondered then that Tokyo assessed India and its government to be not worth the strategic trouble, and reconciled itself to doing things “the India Way” — playing the short game for small gains. Hence, security cooperation is showcased by joint naval exercises and such. When a project with limited impact and then mostly in Modi’s Gujarat is preferred to one that’d have enabled India to secure a versatile flying boat, establish itself as the sole producer of the US-2 aircraft in the world, and to seed a genuine aerospace industry in the bargain, what’s left to say?

Still, if there’s any residual strategic wit remaining anywhere in the Indian government and the military one prays even at this late hour for that wit to manifest itself in a prompt to Prime Minister Modi to try and revive the Shinmaywa US-2 deal even if now India has to pay for it out of its own pocket.